Another week, another AI bomb detonates in my brainbox…

After my last post, I wanted to learn more about ‘AI slop’. I searched on Substack and found the brilliant Jurgen Gravestein – his writing is a tech typhoon for the mind. Jurgen’s article, on AI chewing the cud of its own synthetic data, blasted me in the face. Stephen Moore also rearranged my brain cells this week, waking me up to the AI data heist. I chewed these ideas over with friends, tried ChatGPT for the first time, and I found human comfort in Dr Victoria Powell’s eloquence about Frank Auerbach’s art.

‘When Models go MAD’ by Jurgen Gravestein

In his stunning article, Jurgen asks us a stark question: what will happen to truth, diversity, originality of human thought, if we train next-generation AIs on their own output? These machines learn by processing and spotting patterns in huge amounts of data, but frequently they interpret data wrong: they hallucinate. They also homogenise, deleting nuances of diversity, pasting over with same-same certainty. And as AIs generate more synthetic content, the theory is that they’ll feed on it more too. They will have nothing human left to eat!

As a result of this mechanical cannibalism, Jurgen says MAD could happen. He’s referencing a research paper called ‘Self-Consuming Generative Models Go MAD’.And what does MAD stand for? Wait for it, dear humans, this is not at all horrifying. It stands for ‘Model Autophagy Disorder, a direct reference to mad cow disease, which was caused by cows eating feedstock containing bovine brain matter.’ Computers could lose their minds by consuming their own regurgitations.

Stop. Rewind. Play that again.

First thing’s first – us Brits of a certain age are probably more familiar than others with mad cow disease. In the 1980s and 90s, we were the world leaders in that cruel degenerative brain condition. Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy infected and killed cows, then transferred fatally to humans as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Who doesn’t remember the UK’s Agriculture Minister, John Gummer, posing for the press in 1990 with his daughter? He tried to force feed his child a burger, to prove how safe British beef was to eat. For anyone under 40, little Cordelia Gummer, aged 4, refused the meat, while John tucked in.

Just two years later in 1992, ‘three cows in every 1000 in Britain’ had BSE, caused by feeding infected carcasses to cattle. Mutated proteins made holes in the poor cows’ brains. By 2000, 4.5 million cattle had been slaughtered and 77 people had died from vCJD. It was horrific.

What’s mad cow disease got to do with Artificial Intelligence?

Over to Jurgen to explain. He says we need to wake up now to the ‘enshittification of the internet’. In the race to train AIs harder and faster, to win gold in this 21st Century Iron-Man race, the synthetic supplements are hitting AI’s diet.

‘You’d be surprised, but training models on synthetic data is actually very trendy right now,’ Jurgen writes. ‘Done well, it can actually enhance performance. However, […] research suggests that at a certain point, model makers will see diminishing returns and eventually suffer model degradation. It will happen slow but steady. A process that will incontrovertibly and irreversibly cause the dilution of truth and authenticity online. The hallucinations, fake citations, biases, and empty catch phrases — with every cycle they will get reinforced further, like a snake eating its own tail.’

I asked my friend Amber about fake citations. She works in academic publishing. She told me there’s a real problem in her field with AI-generated hallu-citations – that’s made-up quotes from made-up people from made-up sources, which are spread unwittingly by other researchers, who quote the fake citation in their work. Wow. This 2023 study found that although GPT-4 was an improvement over GPT-3.5, still 18% of GPT-4’s citations were found to be fabricated, compared to 55% with GPT-3.5. And guess who is sifting through the litter? Humans.

In the MAD research that Jurgen Gravestein quotes, the researchers show the hallucinogenic impact on images of people’s faces, when AI models are trained over successive rounds on their own synthetic data. Of course, it’s easy to spot the criss-cross marks on people’s faces with each iteration, but that’s the point in this study – the errors won’t always be this obvious, or even detectable.

The ChatGPT problem

At The Bull last Wednesday, I asked my friend John to walk me through ChatGPT-4o. I’ve had the £37.99 app on my phone for three weeks, but I’ve been scared to venture in alone. With the Christmas revellers at the bar, we went in – trying not to stare at the man in the alpine-cat-on-skis-in-Santa-hat-Christmas-jumper.

Firstly, John showed me a couple of prompts and responses on his ChatGPT app. I was staggered. The words raced on to the screen, seeping below the fold. Then, to test uniqueness, we both put exactly the same prompt into the ChatGPT app on our separate devices: ‘Please don’t give me polished text, but rather three rough-cut distinct ideas on where envy springs from and how we make sense of it in our individual lives’. ChatGPT furiously typed out two completely different responses. They were both organised into three bullet points - but that was the only similarity. I recoiled from my device like a wounded hedgehog.

‘That’s the problem,’ John said. Unique-yet-remixed content. The AI answers were plausible enough. Yes, they were lacking a pulse. But I had to admit, they were workable blocks of text. Oh.

Okay, will you stop with all the doom, my love?

What would Wim Hof do?

Breathe in.

Hold for ten.

Plunge head in ice hole.

Swerve heart attack.

Towel dry.

Sweatband up.

Hit the sauna.

Channel John McEnroe in 1981.

Roar!

Actually rather cheesed off now

That’s British for I’m totally pissed, man!

These revelations could have me raging in my cinema seat, pelting popcorn at the screen.

But I’m a geriatric mother who loves her simple carbohydrates.

So, what to do now?

To fight is to read and write

In ‘You’re not pissed off enough about the AI data heist’, another eviscerating piece of human writing, Stephen Moore fired me up. Stephen writes about the ‘first great data heist’ being pulled off by Facebook, and now AI companies have committed ‘the second great data heist, although this time, the safe was emptied before we even realized it.’

‘When the first AI chatbots dropped into the mainstream, there was equal parts fascination and trepidation. Then came the penny drop – what data did they train these things on? And we realized at that moment that we’d been robbed again. They’d gobbled up almost everything. In fact, they’ve consumed so much of our output — our videos, our writing, our art, our photographs, our code — that they’ve got almost nothing left to use.’

And this too from Stephen…

‘A few overlords took everything we’ve ever made, with literal blood, sweat and tears, and threw it into a database, all so some AI bot can regurgitate it back to us, minus all the beauty and craft, and with all the hallucinations of someone on acid whose brain just melted.’

Fuck an absolute dynamite duck. It’s an awareness bomb for me. Here comes the radical refabrication of society (perhaps even nature?) as we know it.

So, where’s the hope shot?

Processing this news, I am asking myself questions:

Do I care about the beauty of original human thinking and creativity? Yes I do.

How can I do my bit to preserve human thinking and creativity?

How can I respect my tiny corner of our internet garden?

And what’s my part in caring about our shared spaces in real life?

What to do about AI Sloppification?

I’m starting with what Geoff, a media company investor, said to me at the Pig and Abbot pub. He said humans need to become curators of quality content. Geoff, I feel it! As Artificial Intelligence’s prolific outputs flood our world, it’s obvious that people who care about original human thinking need to become custodians of creativity.

The hope of card-carrying consciousness

And I loved this comment from Phil on my last Substack post, Subservience v. Super-sentience. Let’s go for the rise in human consciousness, kids!

Phil wrote: ‘I (optimistically) think that AI won’t render the human race completely redundant, but see it as possibly the catalyst to elevate humans to a higher level of intelligence and consciousness. We will need to raise our game in areas that AI can’t (yet) fathom – the very things that make us feeling, imaginative, intuitive beings. Until AI can inhabit an organic physical body and experience the feelings and intuition of a human, then it will inevitably hit an (albeit high) glass ceiling in terms of its knowledge and understanding.’

For now, I need to think about my values, in order to use AI technology ethically

I need to:

respect our public spaces, particularly online – quality over quantity feels guiding

use AI in a way that doesn’t pollute our shared spaces with AI slop

make sure I don’t mispresent, plagiarise, or spread false information – that might not always be easy to spot; the power of the pause before publishing could help me

acknowledge mistakes I make as I learn - to err is human, but let’s go full TTT (Tell The Truth) when I mess up

stay tuned into changes going on in our shared spaces in real life – billboards, big screens, bus advertising, content in retail and leisure spaces, AI cats skiing on our Christmas jumpers, and soon embodied AIs.

be energy-conscious with power-crazed AI tools

keep working the muscle of my critical thinking

continue to cheer and share and buy the work of talented humans

retain healthy scepticism and laugh a lot

believe in human power to shape our collective future

and sleep!

I can start with the basics of better labelling.

AI experts, please help me out here. Transparency feels vital – for example, if I’m using Generative AI images, I can put a caption beneath the picture, and I guess I need to label the image file too, to state explicitly that AI made it. Is that right? Jurgen, Stephen, please send me the manual on this.

Secondly, when I explore AI technology for this Substack, I will be explicit about what I have used and what exactly AI has produced.

I’m seeing those massive hands people take to big stadia events – I need some of those to point out any machine-generated elements.

Finally, as a writer, I’m not going to use ChatGPT or other AI tools to generate new creative writing for me.

Admin and general search tasks, sure – it would be great if ChatGPT could help me stop dropping balls with my work, parenting, study and social commitments. I think it’s fine for ChatGPT to point me to source materials online, in the same way as Google does now. But no thanks to doing my critical thinking or creative writing. Why? Because I need to write that first draft noise out of my head. I have to declutter my brain to understand what I feel, and to focus my errant attention. I often have to sit with intense fear of the blank page. It takes time for ideas to bubble. I edit for days, sometimes weeks. Then I have a finished, imperfect piece. I know this makes me a slow and uncompetitive writer now – so be it.

Use it or lose it

I need to keep the generative part of my brain in shape, otherwise it will shrink to a button mushroom. If I don’t use my creative faculties, I will lose the music of my mind. If I outsource my creative work, gradually my ‘AI assistant’ will enslave me. Then my head and my wallet are screwed – did you hear the one about the $200/ month ChatGPT subscription fee? That’s my electricity bill.

Also, get this – aside from the Prologue to The Coming Wave, even one of the creators of 21st Century AI, Mustafa Suleyman, says he didn’t use AI at all to write his book. If AI copywriting is so great, why didn’t Mustafa employ a machine? The answer is simple, really - he thinks his own thinking is better!

Look, I’m new in this AI ocean…

I am feeling my way, so things may change as I understand that this isn’t the end of civilisation as we know it. But for now, I need human writing more than ever. I am craving the wonder of human art.

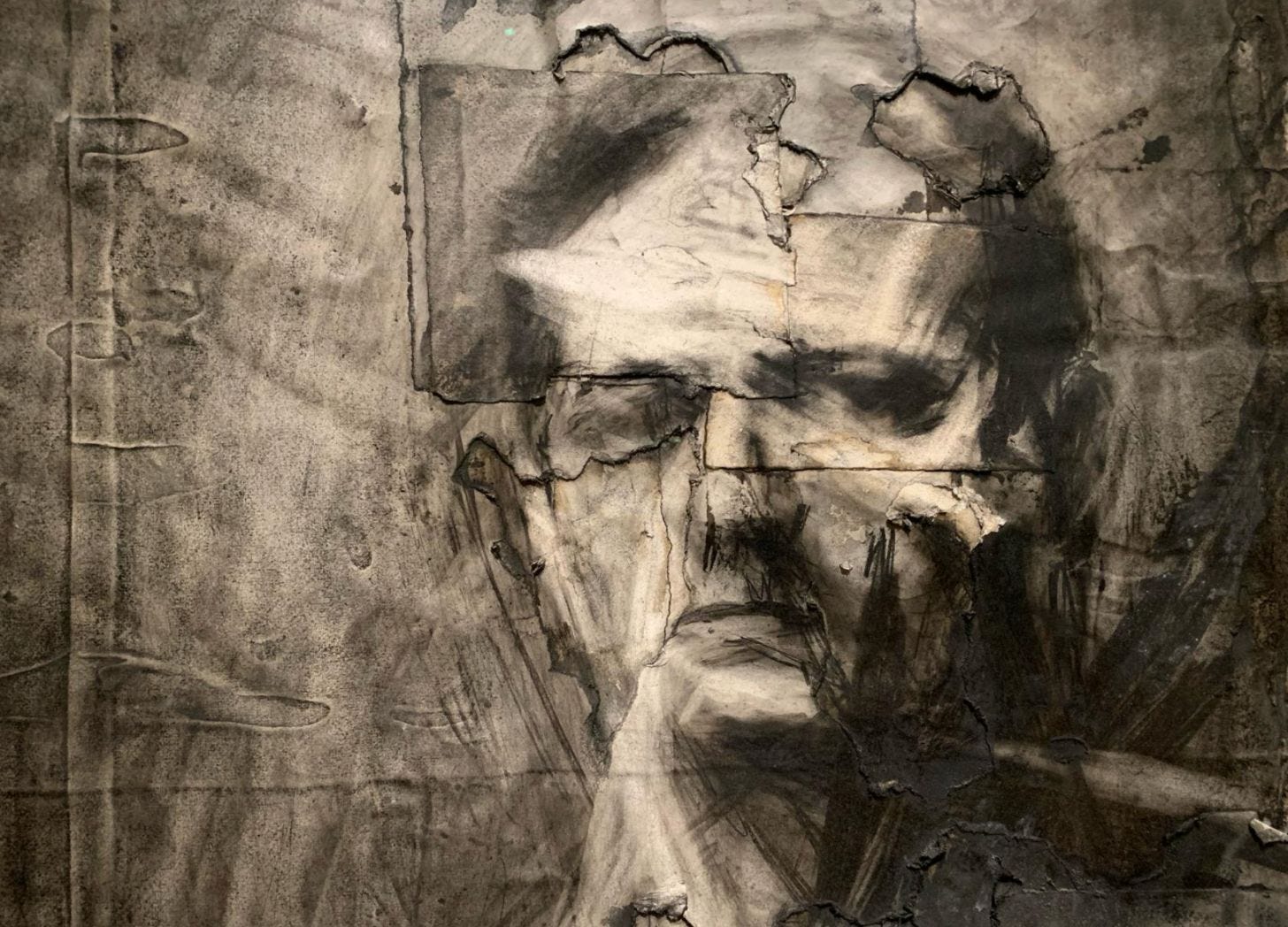

This lovely piece by Dr Victoria Powell about the invisible lines that impact our world calmed me down this week, centring on Frank Auerbach’s charcoal drawings. Victoria moved me with her words about the dedication and craft in Auerbach’s work:

Auerbach ‘would draw the faces of his sitters over and over again, spending hours on a portrait only to rub it out, unsatisfied, and to start again all over. He would use the same piece of paper, which would disintegrate through this process of constant erasing over months. He just patched up the bits of paper that had fallen apart and carried on.’

That’s the blood, sweat and tears that Stephen Moore writes about - here it is, right here.

We need to stare into the shifting faces of Artificial Intelligence with the same clarity and commitment that Auerbach gave to his privileged subjects.

To buy my a tea, a teapot, or a tea plantation, to support my writing, please visit my Buy Me a Coffee page.

With thanks and respect to the humans who informed this piece

Jurgen Gravestein – I am loving your Substack, Teaching Computers How to Talk. Thank you for your kaleidoscopic word mines and dopamine-discovery bombs.

Stephen Moore on Trend Mill – thank you for your gritty spirit, lively language, and knockout punch on tech.

Phil Bourne sells vintage and vintage reissue guitars at 20th Century Toys and he takes portraits of real human beings.

At the Gallery Companion, Dr Victoria Powell writes expressively about art and its meanings – for the art-curious like me, it’s a refreshing and inclusive read.

And to the friends and strangers who gave me illuminating insights that informed this piece – Amber, John, Geoff, the AI researchers, journalists, and yes, Mustafa Suleyman once again – thank you for your human brains that helped me think things through.

Thrilling essay, connecting so many thoughts, ideas, weaving in personal experiences and a jolt of humor! A joy to read, truly.

I agree that there is a beautiful process that happens internally when you work and rework your writing or art. We see patterns, deeper meaning and ultimately our connectedness. By choosing to write something using chat CPT would lose this distillation and clarifying process.